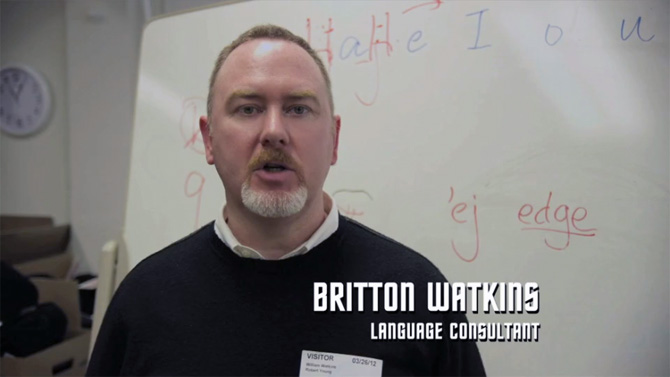

| 1) Use of the object prefix ‹n’› |

1— Is t’Lesterai-faterek ik °N’° |

| Several site visitors have asked via comments and private messages about some of the aspects of grammar that they see used in the dialect here. There are specifically 5 points that should be called out and explained to help new learners and experienced speakers and writers of Modern Golic Vulcan become comfortable with the language they will encounter at Korsaya.org. |

Ki’deshkal pohl-yaretsu na’nash-shi bai’tuhskaya eh awek-skladan pa’ein-pulva t’zhit-isan ik gla-tor ta la’is-tor na’nash-gen-vuhnaya. Nam-tor kau-tatayan-ong ik dang-bolau sasfekau eh starpa’shau na’lof gol-tor n’uzh-orensu eh n’staribsu eh kitausu t’Iyi-Gol-Vuhlkansu ik ma veshtaya ta shetau mohk-yehat k’nash-gen-lis ik dungi snagel-tor la svi’Korsaya.org. |

| This prefix is likely the aspect of this site’s dialect that the experienced will find the most different and unusual. It is derived from the prefix ‹na’› which is very common in Modern Golic Vulcan, but is not a mere abbreviation or contraction of that prefix, but rather performs an entirely different function. It marks the object of a non-passive verb when the subject of the action is not stated explicitly. In this role it bears a resemblance to the accusative case in some languages. This distinction still remains in English as “I want X” contrasted wth “X wants me”. Golic Vulcan would express these short sentence normally as °Aitlu nash-veh X° and °Aitlu X nash-veh° respectively (with no change in °nash-veh° for “I/me”. However, because Golic Vulcan is pro-drop (meaning that it does not require pronouns to be expressed when they are clear from context), it is quite easy for ambiguity to arise. Does °Aitlu nash-veh° mean that someone or thing wants me, or that I am doing the wanting? The ‹n’› prefix clears up this question by overtly showing when a subject has been omitted. |

Kesing nam-tor nash-faterek pulva t’genvuhnaya t’nash-shi ik dan-ritsuri-natyan na’veshtausu. Tveshu faterek ik °NA’° ik maut-tsukik na’Iyi-Gol-Vuhlkansu, ki ri e’nam-tor zhipenaya il pinut t’ish-faterek, ki keing torper-tor natya-is-lof ovsotik. Ulidau n’lesterai t’torupik-tor-zhit ish-wak ri nam-tor pa’shi-star-krus t’navel t’torai. U’nash-pershul ma n’kahkwa’es na’iswaku t’lesterai t’ein-gen-lis. Wi i’hafau nash-natyan-ves na’FSE u’pi’zhit’bal ik °I want X° ik kelam-tor tehnat °X wants me°. Tsuring satiben Gol-Vuhlkansu nash-zhit-bal penik u’nash ik°Aitlu nash-veh X° heh °Aitlu X nash-veh° fupa s’zek | k’rubah na’nash-veh u’zhit ik °I/me° rim |. Ki, fayei nam-tor Gol-Vuhlkansu gen-ves ik nelau n’ulef-vel-zhit — tvai n’ta ri ya’bolau n’ta satiben n’ulef-vel-zhit ish-wak pa’shik s’ek’sitra-klai — nam-tor ved velik ta ma n’paresh t’ond’ohan. Tvai zhit ik °Aitlu nash-veh° ta aitlu veh il ein-vel nash-veh il ta veh ik aitlu nam-tor nash-veh, ha. Sapa’shau faterek ik °n’° ond’ohan bai’ta tu’ashing gluvau n’wak ik ki’nelal n’navel. |

| The Pronunciation of this ‹n’› varies with the phonemes it encounters to its right as does that of other purely consonantal prefixes. Note: ‹n’yon› ››› /ɲon/ for OBJ-burning/blaze with no epenthetic schwa (ə). |

Vuhnau salasharaya t’nash-faterek ik °N’° bai’ralibi ik snagel-tor na’gas-rak u’vath-faterek ik drom-ikastarzun. Beglana’uh— shetau °n’yon° ››› /ɲon/ rik’hayai-ralash ik °uh° /ə/. |

| 2) Dependent Clause Markers ‹Ik› and ‹Ta› |

2— Ulidar t’Ner-zhirabal ik °IK° Heh °TA° |

| Korsaya.org has not been able to locate the VLI “coming soon” lessons on complex sentences in Golic Vulcan. It is assumed that they were never published. However, example sentences reveal the existences of ‹ik› (that, which (relative pronoun) and ‹ta› (that (conjunction)). Both are used extensively here. Examples: |

Riwi vesht kup-tal-tor Korsaya.org tupa t’Shi-Oren Vuhlkansu ik wimish “coming soon” pa’wehkon-zhit-bal t’Gol-Vuhlkansu. Ki’miyusal ta worla ki’saladal. Hi, ahklavau zhit-bal t’li-fal nam t’dah-zhit ik °IK° ik ulef-vel-zhit tomik heh °TA° ik naf-zhit. La’is-tor n’on k’ashiv. Li-fal: |

Vesht nam-tor yar-le-matya ik stal Stonn.

It was a green le-matya that/which Stonn killed. |

Vesht nam-tor yar-le-matya ik stal Stonn.

It was a green le-matya that Stonn killed. |

Illustration by Ani • Var-bikuv s’Ani |

| But note: |

Beglana’voh— |

Vesht nam-tor yar-le-matya ik stal n’Stonn.

It was a green le-matya that/which killed Stonn. |

Vesht nam-tor yar-le-matya ik stal n’Stonn.

It was a green le-matya that killed Stonn. |

Rok-tor nash-veh ta ak’kup-ragel-tor etek.

I hope that we can meet soon. |

Rok-tor nash-veh ta ak’kup-ragel-tor etek.

I hope that we can meet soon. |

Tor-yehat ta ak’kup-ragel-tor etek.

It is possible that we can meet soon. |

Tor-yehat ta ak’kup-ragel-tor etek.

It is possible that we can meet soon. |

Sanoi ta ak’kup-ragel-tor etek.

It pleases (is agreeable) that we can meet soon. |

Sanoi ta ak’kup-ragel-tor etek.

It is agreeable that we can meet soon. |

| ‹Ta› can also function as a substitute for gerunds when the verb in the gerund needs to take objects. |

Kup-vath’kizh-tor n’zhit ik °TA° na’torvel-zhit isha ish-wak bolau tor-zhit t’torvel-zhit el’tanarau is-vel. |

Tal-tor n’yeht-kilkaya bai’ta deshkau n’yeht-suyu yehting.

(One) finds the correct answer by asking the correct people properly. |

Tal-tor n’yeht-kilkaya bai’ta deshkau n’yeht-suyu yehting.

(One) finds the correct answer by asking the correct people properly. |

| Alternately for the same meaning without ‹ta›: |

Krusiting na’ka-tvah rik’zhit ik °TA°— |

| Tal-tor n’yeht-kilkaya bai’yeht-deshkaya t’yeht-suyu. |

Tal-tor n’yeht-kilkaya bai’yeht-deshkaya t’yeht-suyu. |

| The marking of ‹ta› with ‹n’› is common with omitted subjects, but not mandatory. Where two dependent clauses might occur together, it is more common for the subject to become a gerund. |

Nam-tor ulidaya t’zhit ik °TA° bai’faterk ik °N’° tsurik ish-wak ri ma n’navel, hi ri ya’bolaya. Ish-wak lau-paresh-tor dah-ner-zhirabal teretuhr, weh-tsuring shetau navel torvel-zhit. |

Vesht aisha shaya t’makh ta wa’stron-tor sov vi’tvi-shal.

Breaking the glass caused the air to escape (explosively) into the chamber. (Lit: The breaking of the glass caused that the air escape (intensely/greatly) into the chamber.) |

Vesht aisha shaya t’makh ta wa’stron-tor sov vi’tvi-shal.

Breaking the glass caused the air to escape (explosively) into the chamber. |

| Additional note on the use of ‹ik›. ‹Nam-tor› in the role of the the copula is almost universally dropped after ‹ik›: |

Hayai-pitoh pa’is t’zhit ik °IK°— Enem-tor n’zhit ik °NAM-TOR° u’naf-tor-zhit po’zhit ik °IK° siyah ek’ovsoting. |

Nam-tor T’Lin ik otrensu t’nash-trahokna ko-kuk t’nash-veh isha.

T’Lin, who is the Master of this institution is also my aunt. |

Nam-tor T’Lin ik otrensu t’nash-trahokna ko-kuk t’nash-veh isha.

T’Lin, who is the Master of this institution is also my aunt. |

| 3) Adverbs Formed with a Suffixed ‹Ng› |

3— Nosh-zhit ik Shidorau

3— k’Raltvah-krus ik °-NG° |

| This site’s dialect forms adverbs ending in ‹-ng› out of standard adjectives that end in ‹-ik› fairly productively. You may not find these consistently noted in any dictionary, but the meanings are predictable based on the adjectival forms. |

Shidorau gen-vuhnaya t’nash-shi nosh-zhit ik shahtau k’raltvah-krus ik °-ng° s’rub-zhit ik shahtau k’raltvah-krus ik °-IK° toming torvaing. Lau-pavesh-tor ta ri kup-tal-tor n’nash-faika-zhitlar svi’zhit-dunap, hi kup-kriltesau n’tvah s’rub-zhit-shid. |

| 4) The Adverbial Prefix ‹E’› |

4— Nosh-zhit-faterek ik °E’° |

| Like the adverbial prefixes ‹i’›, ‹la’›, ‹wa’›, etc., the morpheme ‹e’› can affix directly to a verb to convey the sense of “only, just, simply”. Compare the free adverb form ‹goh›. Example: |

U’nosh-zhit-faterek ik °I’°, °LA’°, °WA’°, k’ka-vehlar, kup-kifau raltvah-krus ik °E’° na’tor-zhit na’lof zhelesh n’tvah ik °goh, veling, nening°. Li-fal— |

E’nam-tor kisheya.

It’s just an accident. / It’s merely an accident. |

E’nam-tor kisheya.

It’s just an accident. / It’s merely an accident. |

| Note: The sense of immediate past in FSE (“That just happened (a moment ago).”) is NOT conveyed by this prefix. |

Beglana’voh — Ri zhelesh nash-faterek tvah t’FSE ik sagluvau n’iwi-vesht u’nash ik °That just happened (a moment ago).° ik tvah ik °Iwi-vesht pavesh-tor ish.° |

| 5) The Verb Prefix ‹Dang-› |

5— Tor-zhit-faterek ik °DANG-° |

| Like the verb prefixes ‹kup-›, ‹lau-›, etc., the element ‹dang-› can affix directly to a verb to convey the sense of “ideal course of action”. It is generally translated as “should”. Compare to ‹vun-› (must) and realize that ‹dang-› is similar in feeling to this prefix, but weaker. Example: |

U’tor-zhit-faterek ik °KUP-°, °LAU-°, °WA’°, k’ka-vehlar, kup-kifau zhit-krus ik °DANG-° na’tor-zhit na’lof zhelesh n’tvah t’°tangu-torai-dotoran°. Mesukh-tor paing u’zhit t’Fse ik “should”. Navatha’voh na’faterek ik °VUN-° heh ken’voh ta ma n’kahkwa-olaya, nam-tor weh-kobatik. Li-fal— |

Dang-stariben du.

You should speak. |

Dang-stariben du.

You should speak. |

Vun-stariben du.

You must (have to) speak. |

Vun-stariben du.

You must (have to) speak. |

| If you have any questions about these dialectal variations or other differences you find here, please do not hesitate to inquire at the address provided in the Contact section of this site. |

Kuv ma tu fan-deshker pa’nash-natyan t’gen-vuhnaya il vath-natyan-ves ik la’tal-tor — sanu — ri ma’voh fan-vaunah pa’ta deshkau fna’krus t’mestaya t’nash-shi rim. |